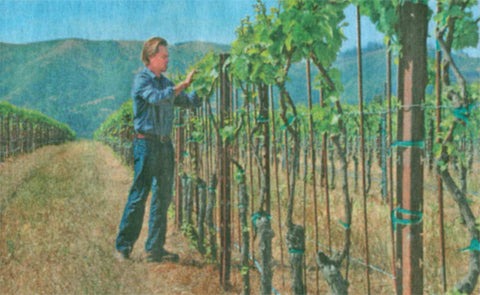

MIKE ELIASON / NEWS-PRESS

By GABE SAGLIE

NEWS-PRESS CORRESPONDENT

Thursday, May 2, 2013

Local Winemaker Turns Grape Growing Upside Down

If necessity is the mother of invention, then winemaker Bryan Babcock may be mother's little helper.

After more than five years of experimentation and plenty of trial-and-error, the celebrated Lompoc-based winemaker is touting a new way of farming wine grapes. It's a series of practices and gadgets for which federal patents are pending.

But what they suggest - the way that they revolutionize an established and widely used method of growing fruit - could turn the industry on its head, quite literally: grapevines are grown from the top down, rather than from the bottom up.

They're ideas that Mr. Babcock, himself, thinks his Santa Barbara County colleagues would label "crazy."

Finally confident in his findings, Mr. Babcock, 53, is just now sharing his findings in earnest.

The actual necessity in this story was a fiscal one. With the domestic economic dive that started in late 2007, "everything came to a stop," he recalls.

There was a major slowdown in consumer demand for higher-end wines, coupled with rampant downward pressure on pricing; he responded by halving his yearly production to 10,000 cases and terminating several grape contracts with other vineyards.

And then he turned his attention to the upkeep of his 65 acres of grapevines.

"My farming costs were out of control," he says. "Pruning was costing me $500 an acre, and it just got to the point where it was simply impossible for me to produce a wine at a $20 price point."

Mr. Babcock, whose family has owned and farmed their Sta. Rita Hills vineyard along State Route 246 since 1979, pinned much of the exorbitant cost of pruning and overall vine upkeep on VSP, or "vertical shoot positioning."

This vine-growing technique trains vines to grow upward, weaving through a wire trellis; this keeps the production canes - the canes from which grape clusters grow - about 21/2 feet off the ground and sends the vine's leafy shoots growing several feet above that.

VSP has been standard industry practice for decades in California, including Santa Barbara County, where it's employed on most every vineyard.

Except Babcock Winery.

Mr. Babcock says his epiphany came when he concluded that VSP isn't natural. Forcing vines upward, he thought, was going against gravity.

"I'd see these long, random shoots growing out and then downward, while everything else was pushed up," he recounts, "and I suddenly said to myself, 'Don't they all want to do that?'"

What's more, he realized that much of his pruning costs were going to battling the thriving shoots that would become gnarled and entangled in the wires.

"It was a constant chase," he says, "pulling and cutting down and even automating."

Slashing back this foliage during a grapevine's growing season is critical to minimizing the threat of rot. But it was coming at a high price.

"So I remember thinking to myself, 'I want to get my vines to suspend in space,'" Mr. Babcock says, his arms outstretched to represent floating vines.

Though actual magic was not in the cards for this winemaker, what he devised may well be the next best thing.

He calls it "canopy pivoting," and that's exactly what his new technique does: it pivots the grapevine upside down. The key is doubling the elevation of his production canes - grapes are now growing at 5 feet off the ground.

During the growing season, the westerly breezes that push in from the ocean bend the vines in the opposite direction and then gravity coaxes them downward; they now grow away from any wires and onto the ground, like a curtain.

To get that critical five-foot height, Mr. Babcock invented a rebar pedestal with a helix-shaped hook at the top that, at about 1.5 inches in diameter, is loose enough to run a grapevine through but open enough to allow that vine to grow.

The pedestals are light - about 1/3 of a pound - and are hung a foot apart. The system - pedestular cane suspension, he calls it - makes pruning easier, and thereby cheaper.

"I've reduced my farming costs by 30 percent!" Mr. Babcock says enthusiastically.

There are also some unexpected benefits, such as the ergonomic perk of allowing crews to pick grapes at eye level, rather than by crouching over.

"Fewer injuries," Mr. Babcock says.

He thinks that the extra height may have recently saved some of his fruit from frost, too. (Cold air generally drops close to the ground.)

And since grape exposure to the sun is now greater, Mr. Babcock has also invented the "helicular shoot hotel," a metal device that attaches to the top of the stakes that hold up the vines and allows him to insert shading material down each row.

The gradient of the netting can be varied to effectively control sun penetration, depending on the time of year or the changing weather conditions of the day. He's dubbed it "shade throttling."

Today, after three years of vine-by-vine conversion, this comprehensive and patent-pending "canopy pivoting" overhaul, which features several other techniques, has taken over the Babcock Vineyard almost entirely.

But its inventor insists that his elaborate creations - rules of physics and mechanics do play a pivotal role - did not come easily.

"I am a farmer who realizes that perseverance is an essential ingredient in what I do," Mr. Babcock says.